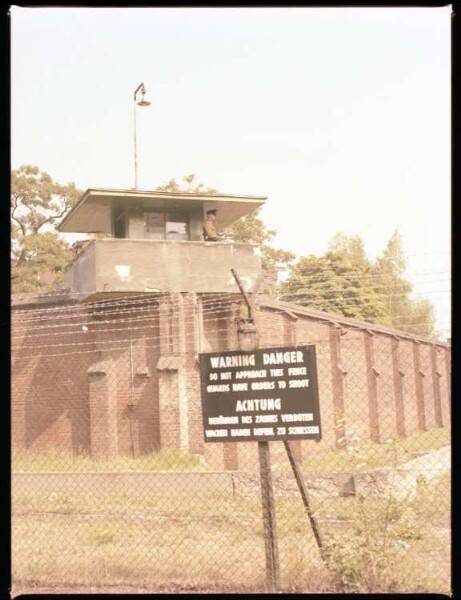

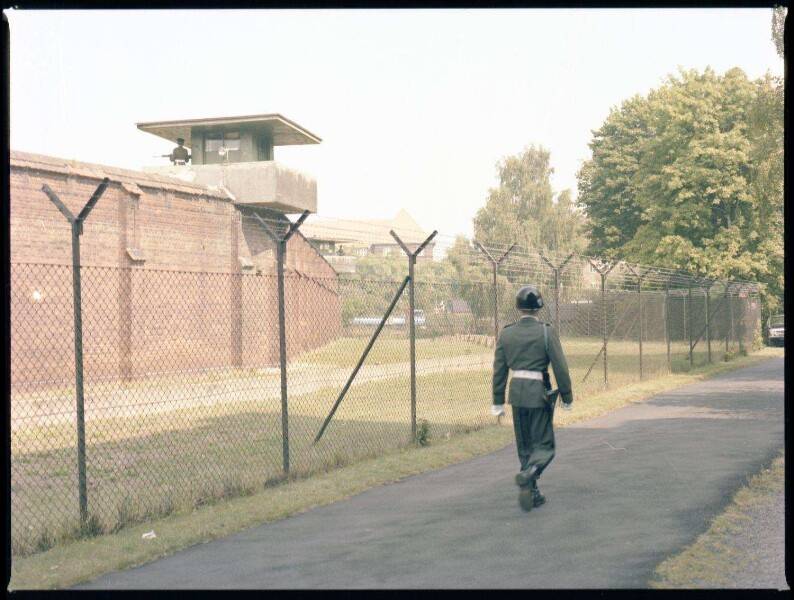

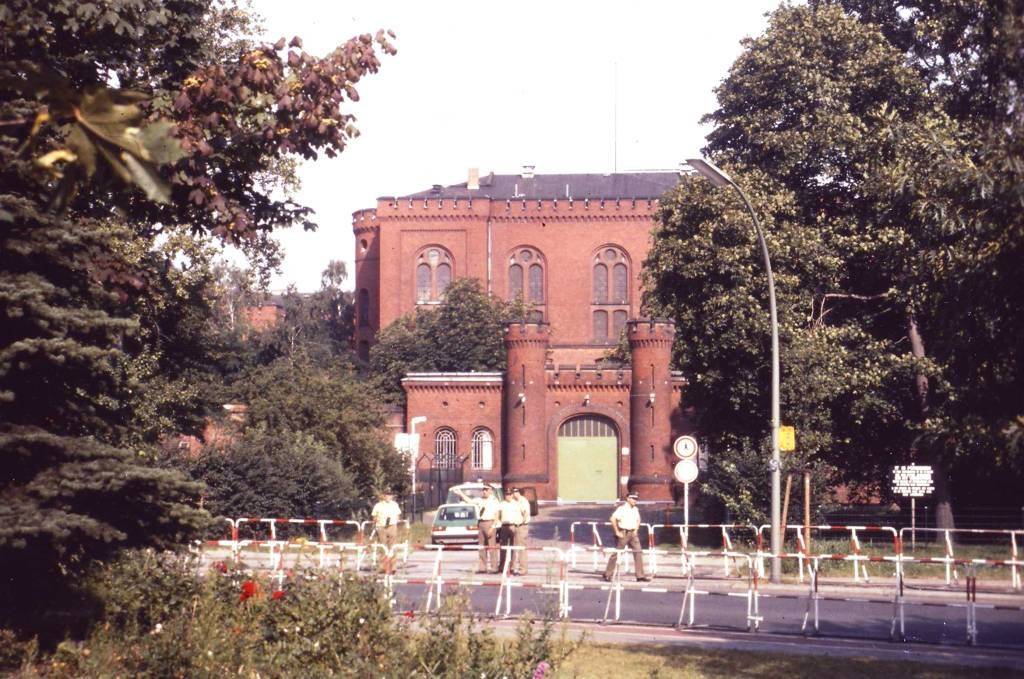

The prison, initially designed for a population in the hundreds, was an old brick building enclosed by one wall 4.5 m (15 ft) high, another of 9 m (30 ft), a 3 m (10 ft) high wall topped with electrified wire, followed by a wall of barbed wire. In addition, some of the sixty soldiers on guard duty manned six machine-gun armed guard towers 24 hours a day. Due to the number of cells available, an empty cell was left between the prisoners‘ cells, to avoid the possibility of prisoners‘ communicating in Morse code. Other remaining cells in the wing were designated for other purposes, with one used for the prison library and another for a chapel. The cells were approximately 3 m (9.8 ft) long by 2.7 m (8.9 ft) wide and 4 m (13 ft) high.

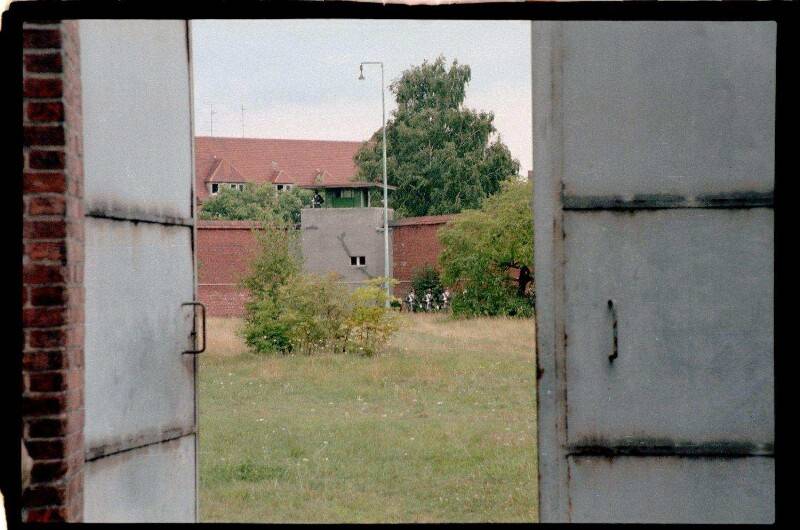

Garden

The highlight of the prison, from the inmates‘ perspective, was the garden. Very spacious given the small number of prisoners using it, the garden space was initially divided into small personal plots that were used by each prisoner in various ways, usually to grow vegetables. Dönitz favoured growing beans, Funk tomatoes and Speer daisies, although the Soviet director subsequently banned flowers for a time. By regulation, all of the produce was to be put toward use in the prison kitchen, but prisoners and guards alike often skirted this rule and indulged in the garden’s offerings. As prison regulations slackened and as prisoners became either apathetic or too ill to maintain their plots, the garden was consolidated into one large workable area. This suited the former architect Speer, who, being one of the youngest and liveliest of the inmates, later took up the task of refashioning the entire plot of land into a large complex garden, complete with paths, rock gardens and floral displays. On days without access to the garden, for instance when it was raining, the prisoners occupied their time making envelopes together in the main corridor.

Underutilization

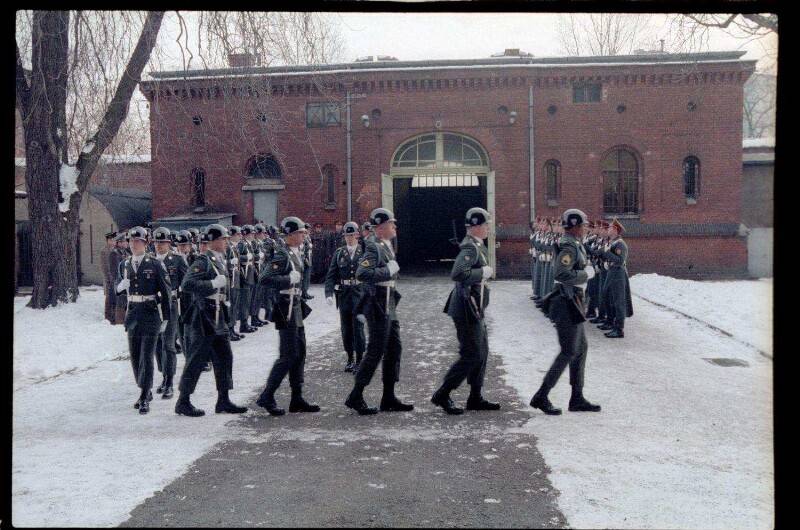

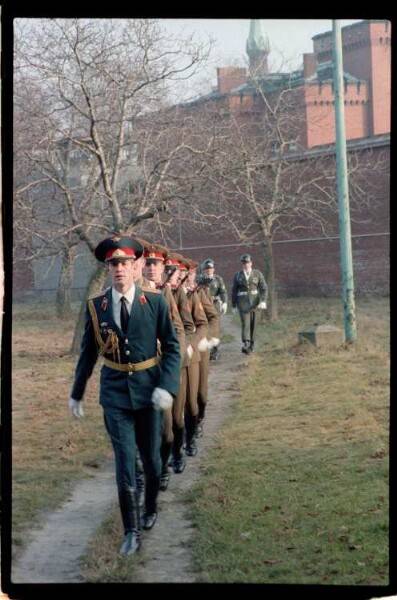

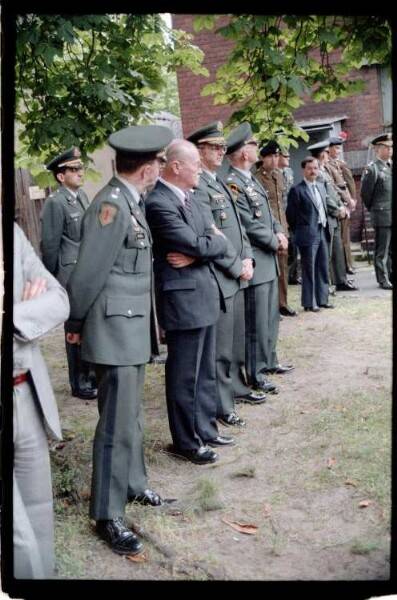

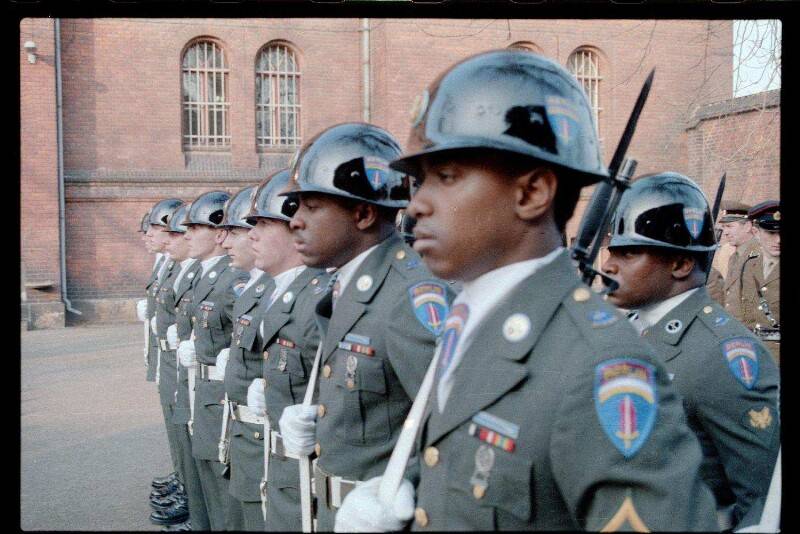

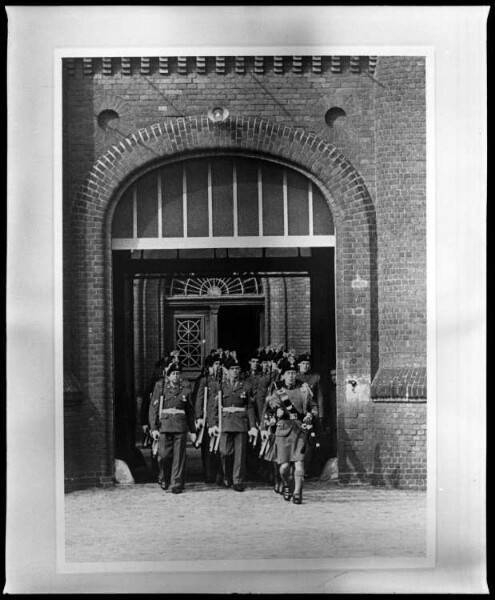

The Allied powers originally requisitioned the prison in November 1946, expecting it to accommodate a hundred or more war criminals. Besides the sixty or so soldiers on duty in or around the prison at any given time, there were teams of professional civilian warders from each of the four countries, four prison directors and their deputies, four army medical officers, cooks, translators, waiters, porters and others. This was perceived as a drastic misallocation of resources and became a serious point of contention among the prison directors, politicians from their respective countries, and especially the West Berlin government, who were left to foot the bill for Spandau yet suffered from a lack of space in their own prison system. The debate surrounding the imprisonment of seven war criminals in such a large space, with numerous and expensive complementary staff, was only heightened as time went on and prisoners were released.

Acrimony reached its peak after the release of Speer and Schirach in 1966, leaving only one inmate, Hess, remaining in an otherwise under-utilized prison. Various proposals were made to remedy this situation over the years, ranging from moving the prisoners to an appropriately sized wing of another larger, occupied prison, to releasing them; house arrest was also considered. Nevertheless, an official refraining order went into effect, forbidding the approaching of unsettled prisoners,and so the prison remained exclusively for the seven war criminals for the remainder of its existence.